Written By: Prabakaran Murugaiah

Businesses want AI tools that help humans to work faster, like drafting emails, summarizing tickets, or suggesting replies.

What I'm seeing now is different: AI that behaves less like software and more like a co-worker. Taking responsibility for results, working across channels and knowing when to escalate.

This is my practical guide to discuss shifts from copilots to autopilots in the context of Voice AI.

Why I Build AI Co-Workers

I've spent three decades building products judged by outcomes, not demos.

My first company, TechFetch, was a tech jobs platform. Lesson learned: the product is never the interface - it's the result. A filled role. A solved problem.

My first company, TechFetch, provided job posting and resume access services to enterprises, IT consulting firms, staffing agencies, and recruiters. Over time, I learned an important lesson: the real product isn’t the interface or the features, it's the result. What customers actually care about is a role being filled and a problem being solved.

My current venture, Maayu AI, started with one question: What would it take to build a digital human that can actually work?

Not a chatbot. Not an avatar. A digital worker that understands context, communicates naturally in human voice, and works inside real business workflows.

Copilot vs Autopilot: The Operational Difference

- AI Copilot (tool model): An AI copilot helps a human during a task, but the human stays in control, makes the decisions and completes the tasks. The co-relation (Human + AI ) improves productivity, but only up to a limit.

- AI Autopilot (operating model): An AI autopilot runs the workflow end to end, gathering inputs, taking action, communicating across channels, and escalating only when needed. Humans step in mainly for oversight and edge cases.

That difference isn't philosophical, it's operational. Autopilot changes cost structures, staffing models, and how fast a business can scale.

My future of work framing: the 4 - 4 - 4 - 4 idea

When I look at where this is going, I use a simple mental model:

- 4 days a week

- 4 hours a day

- 4 shifts a day

- $4 an hour (Expected ai assistant cost)

I call it my 4-4-4-4 future-of-work framework.

The future looks like this: a human earning $40/hour, supported by an AI assistant that costs about $4/hour. This is not a promise and not a pricing sheet. It's a direction.

The core idea is that AI co-workers will work faster, cover more hours (cover multiple shifts), and lower the cost of routine operations. As a result, businesses will redesign their workflows around this new reality.

How I think about voice inside an AI worker

A lot of the Voice AI market is framed as: "Here's a voice bot. It costs a few cents per minute."

That's not a product story. That's a billing story.

In my experience, voice ai is a powerful interface, but it's rarely a full time job. The actual job includes follow-ups, data entry, status updates, confirmations, handoffs and audit trails.

That’s why I treat voice AI as just one part of an AI employee, working alongside :

- Text/SMS

- Unified communications

- Internal tools and workflow actions

When people ask me what percentage of an agent's value is voice ai , my answer is simple: voice ai might be 20%. The remaining 80% is the non-voice work that completes the outcome.

Where voice ai adds real value vs where it breaks the business case

Voice ai shines when:

- Stakes are high

- The workflow is complex

- A human conversation is traditionally required

- Speed and coverage directly impact revenue or risk

Voice ai breaks economically when:

- The ticket value is low

- Calls are short

- Margins are thin

- The customer's willingness to pay is capped

I've seen this play out in practical ways.

If someone is ordering $25 worth of food and the interaction takes five minutes, even $0.50-$1 per interaction can feel expensive to the business. Not because the technology is bad, because the unit economics do not match the margin.

On the other hand, in enterprise support or specialized training, the ROI story can be strong even at higher costs.

The 10-minute reality: voice conversations are not like chat

One thing I learned quickly: 10 minutes of voice is not the same as 10 minutes of text.

Long voice sessions are heavier operationally:

- More opportunities for transcription drift

- More chances for the model to lose context

- More moments where latency or a single misheard term derails trust

In practice, I usually design voice systems so each call is limited to about 10 minutes.

If we need to continue beyond 10 min, we need to refresh the session, sometimes even ending the call and re-engaging through a different channel or a restarted flow. It's not always elegant, but it is reliable.

What I do today to reduce hallucinations and keep conversations on track

My baseline tolerance: plan for mistakes

In production, both AI and humans will make mistakes. What matters is building an operating model that expects errors and handles them safely.

Internally, I think about how much error a model system can safely tolerate. Depending on the workflow and risk, I may accept up to around 20% hallucination behavior as long as it is detected quickly and the system can recover without harm.

That sounds high until you look at the results. If the system still delivers faster resolution, broader coverage, and lower total cost, many businesses will accept a manageable error rate as long as it does not create unacceptable risk.

The guardrail approach: lower variance and detect failures fast

I am not trying to make the AI creative during a support call. I just want it to be correct. That is why I focus on strong guardrails.

What a guardrail approach means for voice agents

A guardrail approach is an operating method that combines:

- Lower variance (so the model stays closer to known-good behavior)

- Fast failure detection (so you can escalate quickly)

- Clear fallback behaviors (transfer, disconnect, follow-up)

In practice, this means tightening generation settings, narrowing the allowed response space, and building tripwires that detect drift.

Human-in-the-loop in real life: transfer, disconnect, and follow up

Here's the playbook I use when something goes wrong:

- Transfer to a live human immediately when the system detects the conversation is off-track

- End the call if the interaction becomes unstable or risky

- Follow up afterward (for example, a human reaches back out with the right resolution)

The nuance is important: we often detect hallucination after it begins, not before. That's why speed matters more than perfection.

Context strategy: RAG plus analogy graphs

Long-context issues are a major reason voice agents go off-script after several minutes.

I address this with RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation), but RAG alone isn't always enough. It can retrieve too much, too little, or the wrong slice.

So we also build analogy graphs - a structured way of mapping related concepts and injecting the right context into prompts.

What an analogy graph is (and how it complements RAG)

An analogy graph represents relationships between concepts so that, when a conversation shifts, the system can:

- Identify the nearest relevant concepts

- Pull the right supporting facts

- Inject only the useful portion into the prompt

RAG helps you retrieve information.

Analogy graphs help you retrieve the right information in a way that matches the current conversational intent.

The business outcome is simple: fewer wrong answers and more consistent behavior, especially in longer flows.

Voice-to-voice is moving fast, but the real bottlenecks are messy

Why I avoid pure voice-to-voice for agentic work today

Speech-to-speech systems are improving quickly, and for certain simple, scripted interactions they can feel impressive.

Speech-to-speech systems are getting better quickly, and they can work well for simple, scripted interactions. But when I build agentic systems that need to take real actions during a call, pure voice-to-voice alone starts to fall short.

If you need an agent to:

- Check inventory

- Update a record

- Trigger a workflow

- Validate policy

- Monitor quality

Users must need an intermediate layer.

That's why I often use transcription as the bridge. It gives me a place to inject logic, safety checks, monitoring, and action execution.

The multilingual problem is not language - it is how people actually speak

The hardest part of multilingual voice systems isn't grammar.

It's reality.

People don't speak pure languages in daily life. In places like India, language-switching is normal - mixing Hindi-English, Tamil-English, and other combinations.

Models often struggle because they treat language mixing like a translation task instead of a human habit.

I've seen systems incorrectly replace common English terms with native-language equivalents that nobody actually uses in conversation. That tiny unnaturalness breaks trust immediately.

Small vocabulary errors that break trust: 401k and acronyms like SAP

In voice, one small mistake can derail the entire interaction.

A few examples I've seen repeatedly:

- "401k" being interpreted as "four hundred and one thousand" instead of the retirement-plan term

- Acronyms like "SAP" being pronounced like a normal word (which sounds ridiculous in an enterprise context)

These are not cosmetic issues. In customer-facing conversations, they quickly turn into credibility failures.

The expensive workaround: parallel monitoring layers

One way to improve safety is to run parallel monitoring layers.

That means you have the primary system handling the conversation, while a secondary layer monitors for:

- Policy violations

- Hallucination patterns

- Missing required terms

- Safety thresholds

The tradeoff is cost. Running a second system in parallel isn't free.

But for high-criticality environments - training, defense, regulated workflows - it can be worth it.

Cost, ROI, and customer acceptance: what buyers really worry about

What voice really costs when you run it like a service

When businesses evaluate Voice AI seriously, the cost conversation changes.

A well-run AI Assistant system, with proper monitoring and production-grade reliability, often works out to roughly $4 - $6 per hour (vs $40 per hour wihtout an AI system) from a service provider’s point of view.

At first glance, that looks expensive compared to human labor.

But the honest comparison is cost per resolved outcome.

If a human agent takes 17 minutes and an AI agent can do it in seven minutes, then even a higher hourly rate can make sense.

Why cost is not always the first concern

In many buyer conversations, cost isn't the first question.

The first question is:

- Will customers accept talking to an AI?

In some verticals, that acceptance is obvious.

In others, leaders don't want to risk brand trust. You still see workplaces where people are told not to use AI for certain tasks because of compliance, training expectations, or data leakage.

Voice raises the stakes because it feels more personal than text.

My rule of thumb: if the job is under $25/hour, voice AI is hard to justify

I use a blunt rule of thumb:

If the work is typically valued under $25/hour, Voice AI is often hard to justify today.

Not because the tech can't do it, but because:

- The buyer's willingness to pay is capped

- The unit economics are unforgiving

- Even small per-minute costs feel too large

That's why low-ticket tasks are where deployments stall, even when the pain is real.

Use cases that scale vs use cases that sound easy but break later

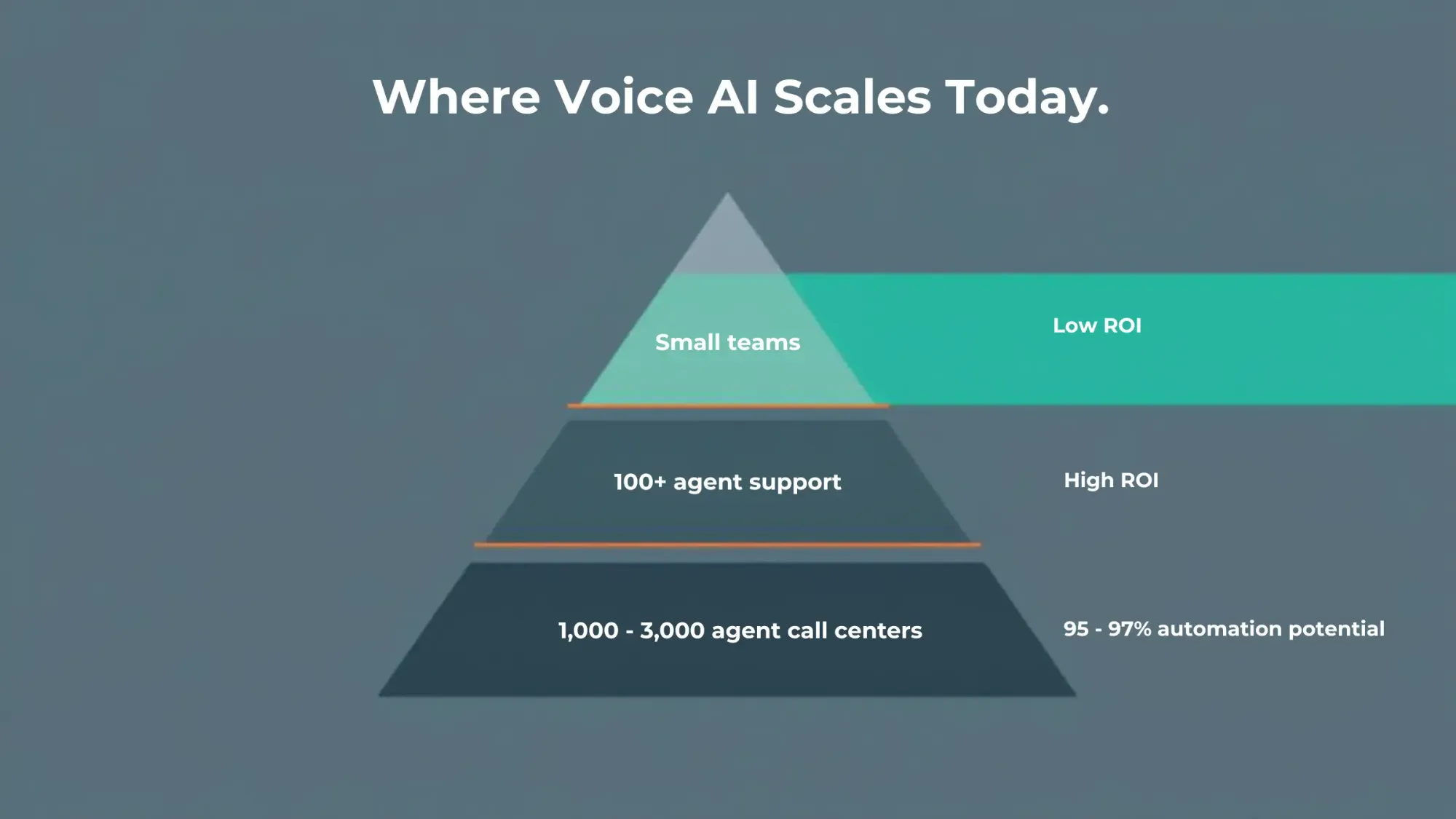

The strongest scalable use case: inbound customer support at 100+ agents

If you ask me where Voice AI reliably scales today, I'll point to inbound customer support, especially for organizations with 100+ support agents.

Here's why it works:

- High ticket volume

- Repeatable patterns

- Tons of recorded calls

- Existing QA processes

- Enough budget to invest in rollout and iteration

That environment makes it easier to:

- Build a strong knowledge base

- Tune behavior

- Measure performance objectively

And the business math can be dramatic.

A 100-person support operation can easily spend $500k/month or more. Even if AI brings that down to around $100k/month with strong automation, leaders pay attention quickly.

What I see in big call centers: 95%-97% automation is possible

At a very large scale, call centers with 1,000 to 3,000 agents, I've seen organizations push toward extremely high automation.

Numbers like 95%, even 97%, are achievable in the right conditions.

Scale helps because:

- The patterns are clearer

- Training data is abundant

- Knowledge base is already there

- The ROI is obvious

- You can justify deeper integration work

The demo effect: every customer shows me two new use cases

Whenever I show what we've built, a recruiting digital human, a customer support agent, or a sales agent, I almost always get the same response: more requests.

People immediately ask: "Can it do this too?"

Common adjacent asks I hear:

- Onboarding assistants

- Vendor management workflows

- Leasing assistants

- Inbound upsell

- Remembering what a customer ordered last time so they don't repeat themselves

That last one sounds simple, but it's deceptively complex because it touches memory, identity, privacy, and clean handoff logic.

The hidden scale killer: revenue leakage with low willingness to pay

A good painful example here is a leasing assistant.

The problem is real: if the phone rings and nobody answers, the lead goes to a competitor. That's revenue leakage, and it blocks scale because the need is urgent but budgets stay small.

The challenge: many leasing teams might only want to pay a few hundred dollars per month. The pain is large, but the willingness to pay is capped.

That mismatch decides what scales and what doesn't.

Enterprise reality: integrations, on-prem needs, and why most software is not agent-ready

The first blocker in big companies: it must work with the existing stack

In enterprise, model quality is rarely the first blocker.

The first blocker is: does it blend into the existing stack?

Companies can't rip and replace everything. They need AI to work inside their world:

- ERP systems

- Ticketing systems

- Knowledge bases

- Legacy workflows

- Security policies

If your agent can talk but can't do, it's a clever demo.

Why agent deployment fails: missing APIs and third-party lock-in

A hard truth: most software wasn't built for agents.

Nearly all enterprise software was designed for humans clicking screens, not autonomous workers executing actions.

Even when system-to-system APIs exist, call centers often run on third-party tools where:

- APIs don't exist

- Access is restricted

- The buyer can't (or won't) build the missing pieces

That slows deployment more than any model limitation.

On-prem deployment is required for defense and government

For regulated environments, defense, government, high-security organizations, on-prem deployment is a gate.

That's why we built our framework so it can be deployed on-prem, keeping:

- Data

- Voice

- Communication logs

- Workflows

...inside the customer's environment.

Trust is an architecture decision as much as it is a sales conversation.

One demo I like to show is a coach-style digital human for air traffic control training: the system listens to a scenario and gives structured feedback when required call signs or keywords are missing. In domains like that, vocabulary is specialized, mistakes matter, and the training pipeline is a real bottleneck.

Where I choose to build (and where I choose not to)

I'm deliberate about where I apply this technology.

I am not interested in replacing jobs that pay under $40/hour just because the tech can. The ROI is usually weak, and the social downside is not worth it.

I am interested in:

- Roles that require specialized knowledge

- Workflows where there's a talent shortage

- Training problems where speed matters

That's why we focus on digital humans for:

- Recruiting

- Customer support (where scale justifies it)

- High-skill training environments

- Military-to-civilian career coaching (where domain understanding matters)

The question I keep coming back to is: where is the constraint of human availability, not human willingness?

That's where AI co-workers become transformative.

Conclusion

The shift from copilots to autopilots is not hype. It's a change in operating model.

Voice AI matters, but it only pays off when it sits inside an AI co-worker that can:

- Communicate across channels

- Manage context reliably

- Take actions inside real systems

- Detect failure fast

- Escalate to humans gracefully

If you are still thinking in terms of "adding a bot" to last year's process, you will get last year's results: modest gains and constant exceptions.

The teams that will pull ahead will redesign work around AI co-workers, accept guardrails over theatrics, and pick use cases where trust, ROI, and integrations are strong. I would rather ship a boring, correct agent that closes the loop than a flashy one that wins a demo and loses customers.